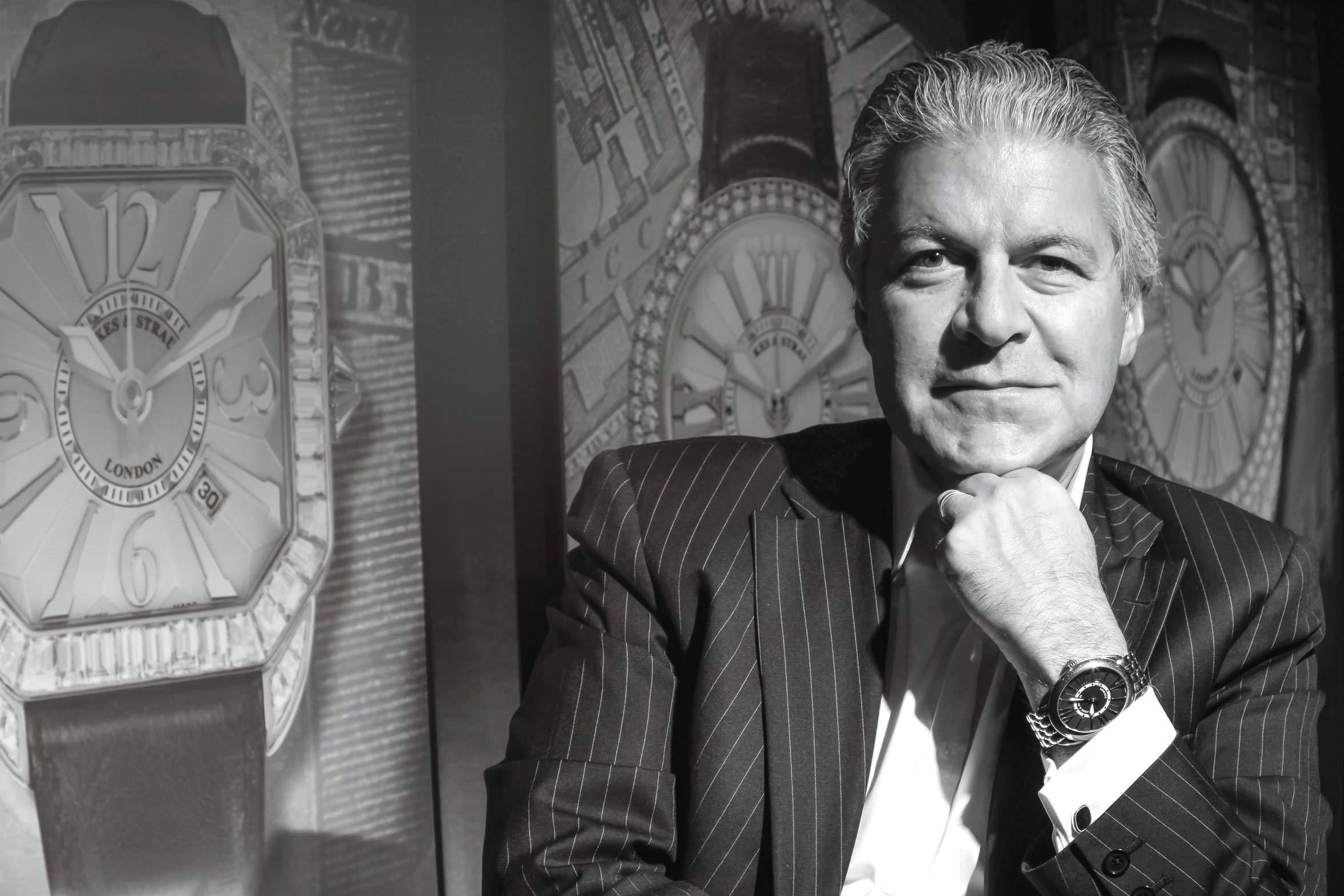

VARTKESS KNADJIAN

“Our story has been one of passion, determination and unrivalled craftsmanship in the pursuit of excellence. As we celebrate our 230th anniversary this year, our mission remains to be the quintessential jewellery timepiece creator, all the while staying true to our four core values; excellence, beauty, innovation and sustainability.”

THE COMPANY LEADER AT THE HEART OF THE BRAND

There is an undeniable element of serendipity in the story of how Vartkess Knadjian came to run Backes & Strauss and instigate its entry into the world of fine watchmaking. We invite you to read more about his long career with the company.

Knadjian Senior

To understand how and why Backes & Strauss came to make wristwatches, we should really look back a century to the birth of Vartkess' father, Antranig Knadjian. Five years before, his family had moved from the Ottoman Empire to Ethiopia where they settled in Addis Ababa. Times were difficult in the Ottoman empire and, not only was Ethiopia a Christian country, Emperor Menelik II was encouraging entrepreneurs and artisans to go and settle down there.

Vartkess' father was born in 1915 and, on the advice of his father who didn't want him to continue studying, left school at the age of 15 and found work as an apprentice watch maker. It was not his dream by any means; what he really wanted to do was to further his education. So, by saving up money made from repairing watches, he was able to afford to enrol in an Armenian school in Paris where he became friends with a fellow student from Geneva who recommended that he try for a place at the city's l'École d'Horlogerie, from which he subsequently graduated in 1939.

One of his final exercises at the school was to make a pocket watch from scratch; every single part had to be handmade by him. Knadjian is pleased to say his late father bequeathed it to him, which, in many ways, has been quite inspirational. It is a gold-cased, half-hunter with an engraved inscription inside the caseback dedicating it to his grandfather.

Vartkess' father left watch making school during one of Ethiopia's more turbulent moments, right in the middle of the second Italo-Abyssinian war, which ran from 1936 - 1941. He went from Geneva to Milan, and from there to the Italian coast where he boarded a boat and got as far as Djibouti.

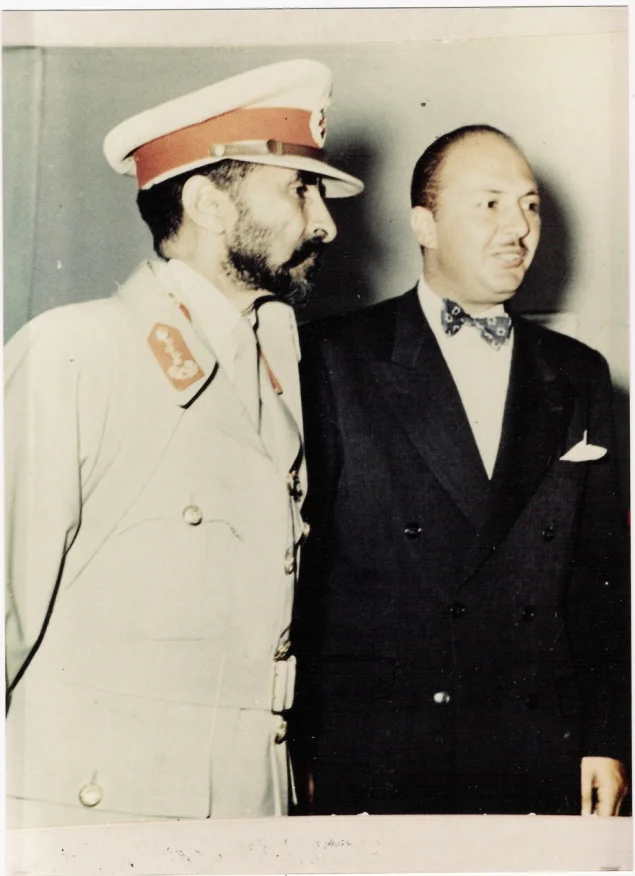

Knadjian senior couldn't go home and was evacuated on to Madagascar. Because he had his watch maker's tools with him, he was able to make a bit of money by carrying out repairs for the crew and other passengers. When he landed on the island, he managed to secure a job in its only watch shop. After two years, with the war in Ethiopia at an end, he returned home and came to the attention of Emperor Haile Selassie who was a great enthusiast of clocks and watches and had somehow heard about Vartkess' father having completed the course at l'École d'Horlogerie de Genève. The emperor encouraged Knadjian senior to go out and build a business selling watches in Ethiopia, and he gradually became the agent for a number of important brands, including Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Jaeger- LeCoultre and the biggest seller of all, Omega.

Vartkess' father was passionate about education and this was a great opportunity for him to go to boarding school in England. But just a week or two before he was due to travel, news came through that his exit visa had been turned down. It coincided with a call from the Imperial Court for a selection of wristwatches to be taken to the palace in order that one could be presented to the wife of General de Gaulle.

While Knadjian senior was delivering the watches, he took the opportunity, for the first and only time in his life, of asking Haile Selassie if he could help with the situation regarding Vartkess' visa. It was delivered to their home the following morning and, as a result, Vartkess was able to take up his place at Kingswood School in Bath.

It was always Vartkess' intention to return to Ethiopia afterwards but, following a gap year, he went on to study at the London School of economics, which was the year before the revolutionary coup, which overthrew Haile Selassie and put the country into turmoil.

The Beginning of Vartkess' Career

Interestingly, these events led for Vartkess joining Backes & Strauss. In 1975, due to not being able to return home, he took a summer job with Ronson Lighters, which had been arranged by then chairman of Ronson Products, William Kenyon Jones, who had become good friends with his father through distributing the firm's products in Ethiopia.

It subsequently emerged that Jones' stepson, George Steer, had gone to work with a friend from Oxford University who happened to be Benjamin Bonas junior, the person who had taken over Backes & Strauss a decade earlier at the tender age of 25. Vartkess was introduced to him by George and, after several further meetings, Benjamin offered him a job working at Bonas and Company, a rough diamond broker through which Backes & Strauss had traded in Antwerp.

Antwerp and the Diamond Trade

It was a fascinating period in Vartkess' life. He spent several months during the summer and autumn of 1976 learning about the trade in Hatton Garden before being sent to Antwerp where he was tutored by the brother of the great Marcel Tolkowsky, the legendary Belgian diamond cutter who is credited with inventing the Ideal Cut.

Being in Antwerp suited him, especially since Britain was going through terrible economic times with high inflation and a declining industry, so he stayed. Vartkess learnt to sort and value diamonds and generally acquired knowledge from some of the greatest characters in the business, which was very different to how it currently is.

Up until the early 1980s, the Antwerp office had been very much a sourcing operation for London rather than being a business in its own right. Suddenly, in 1982, it was left with no one in charge when Christopher, one of the sons of Backes & Strauss' managing director, Robert Lee, left the business to branch out on his own. There was, therefore, an opportunity for Vartkess to take over, and he seized it.

Global Expansion

Knadjian organised the office and, together with Christopher Bull who joined as a trainee in 1982, he built on the London business by adding distribution offices in Toronto, Paris, Los Angeles, Houston, Pforzheim and Hong Kong. They took advantage of the fact that the diamond market had actually experienced a huge crash in 1980 when the speculative bubble well and truly burst; a one-carat diamond, which had cost $6,000 in 1978, for example, had rocketed to $65,000 by 1980. And then the price just fell through the floor.

Backes & Strauss had never involved itself in speculation, which meant there were some great opportunities there for the taking. Benjamin Bonas made the finances available, and - as a result - they were able to grow the business substantially in America, Europe, the UK and, most notably, Japan by doing business directly with jewellery makers and retailers. They were also supplying all the major U.K. and European players, ranging from Cartier, Boodles and Asprey to Garrard, Ratners and H. Samuel.

By the late 1990s, however, the entire diamond trading business had changed significantly following the restructuring of De Beers and the 'supplier of choice initiative'. As a result, many trading companies disappeared and billions of dollars were lost. Due to the way the business was evolving, it became difficult for Benjamin Bonas to be both owner of Bonas and Company and Backes & Strauss, which operated at different levels of the supply chain.

When Life Comes Full Circle

It was because of this that Knadjian was able to acquire Backes & Strauss in a management buy-out. In order to remain sound, it was apparent that Backes & Strauss would need to sell products rather than just polished diamonds and they realised that this could be done by leveraging on its long history and unique heritage.

The initial thought was to make jewellery, but by that stage, they had developed a strong relationship with the Franck Muller Group as a supplier of diamonds for setting in watches. The renaissance of the mechanical watch was well underway, so it seemed logical to combine their considerable experience with precious stones with the chance to leverage Franck Muller's watchmaking expertise and resources to make Backes & Strauss what it is today.

In a sense, it seems Vartkess' life has come full circle from that day in 1967 when the Emperor Haile Selassie enabled him to leave for England to receive a good education, for the simple reason that he and his father had a mutual love of well-made clocks and wristwatches.